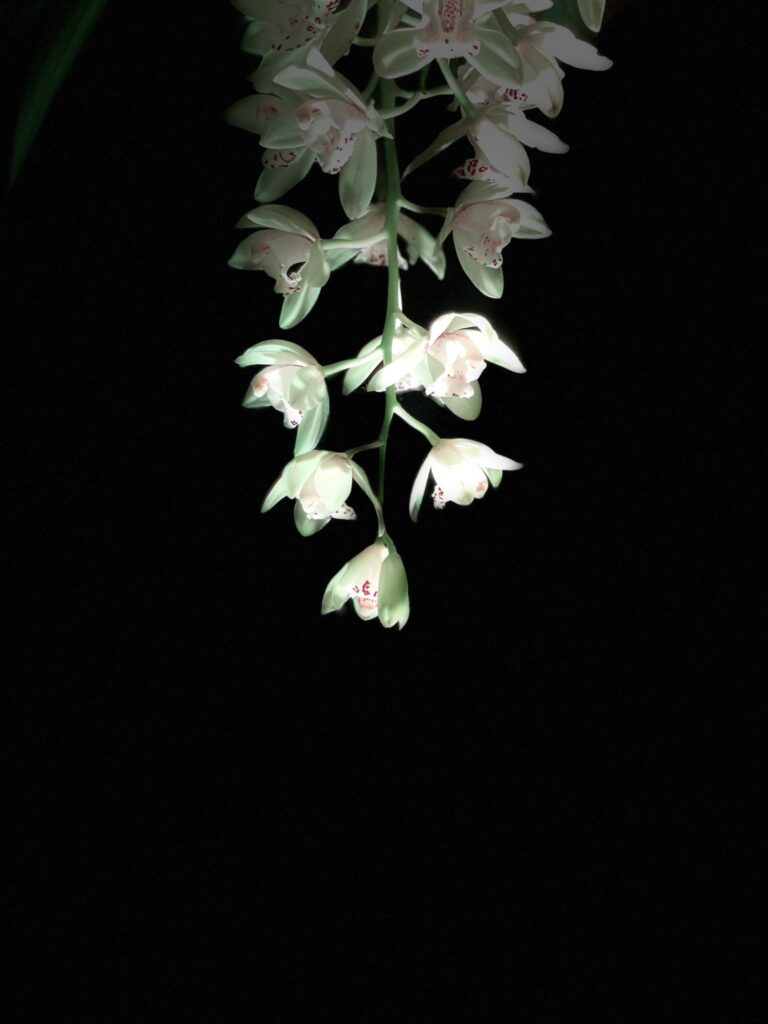

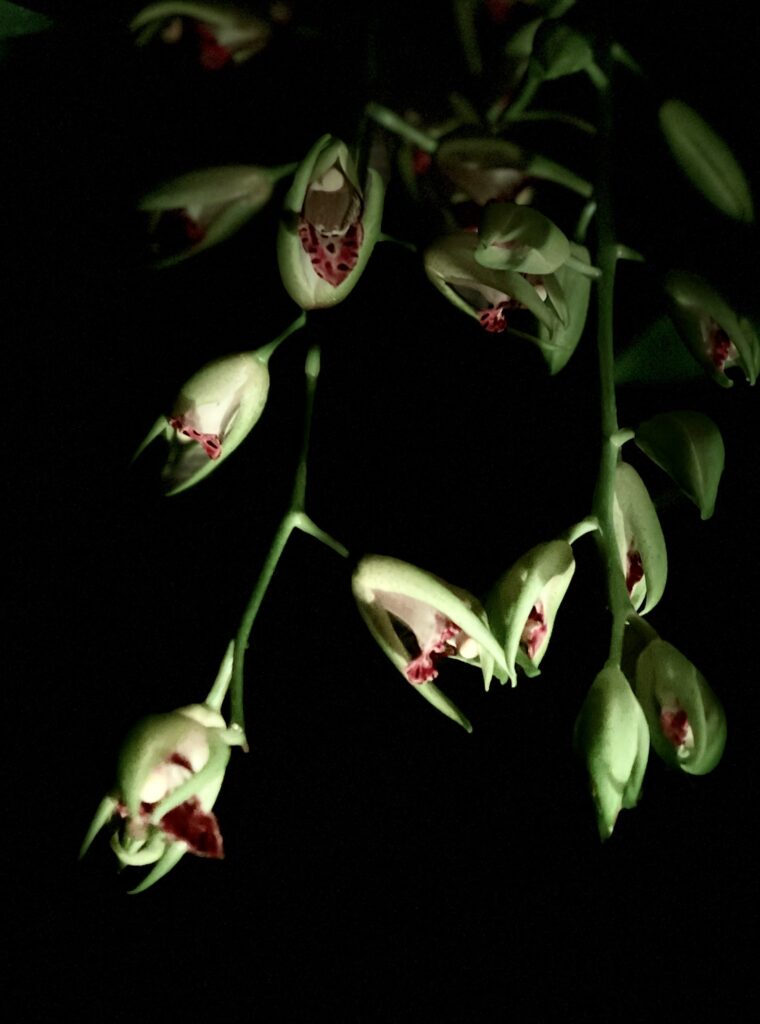

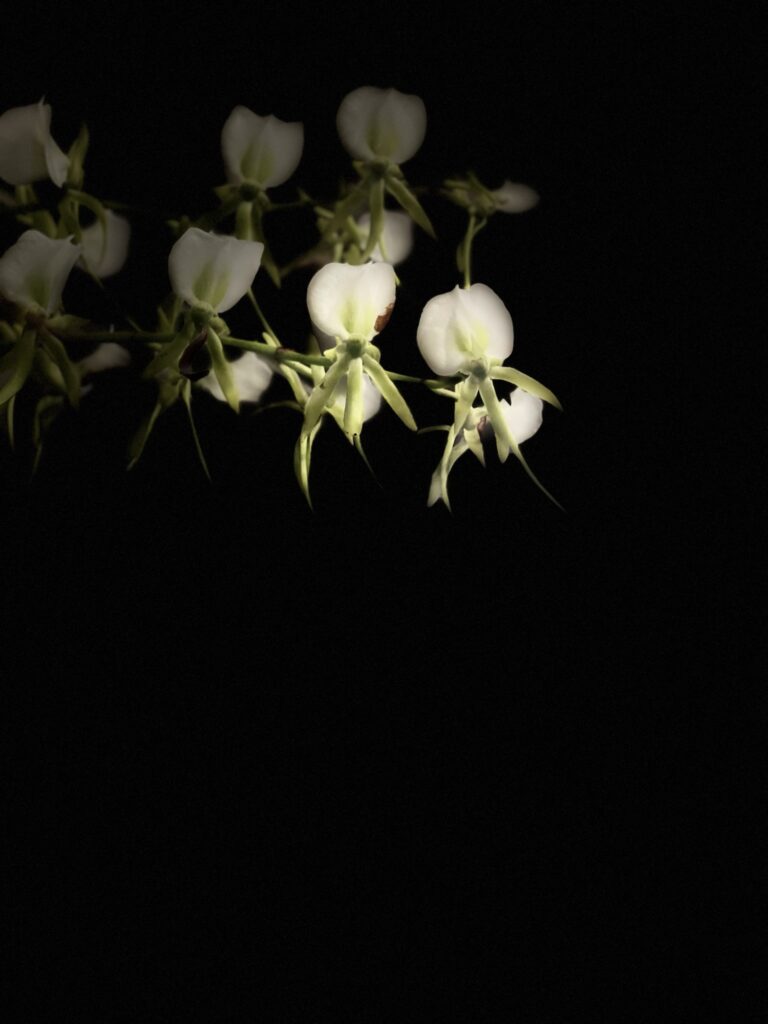

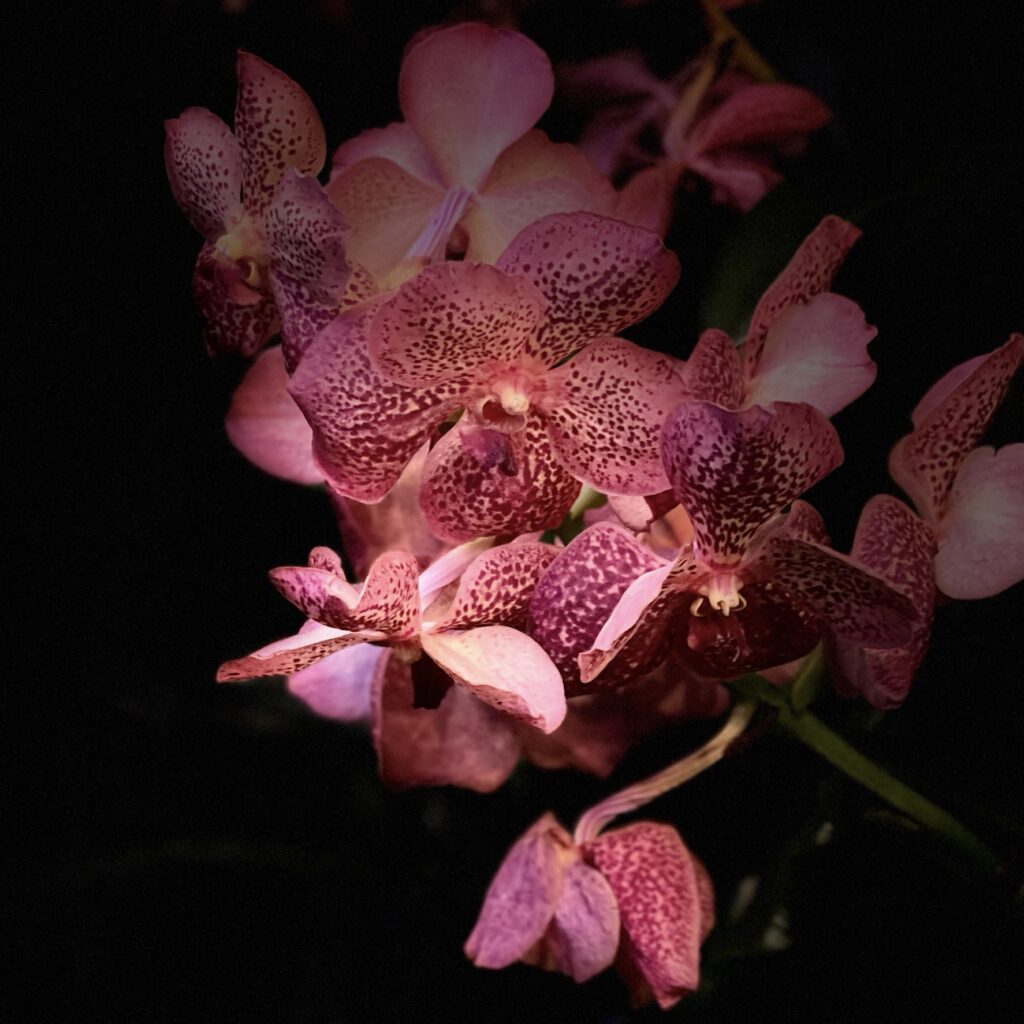

We hoped to visit the orchid festival at Kew with Sue, but she was sick and could not come. Therefore, I decided to go alone and describe them to her.

If plants were conscious and could be intelligent, orchids would be the wisest of them all.

“Orchids – are tropical plants with bizarre and fragrant flowers,” – says the dictionary. However, to me, the biology of orchids is even more extravagant than their flowers.

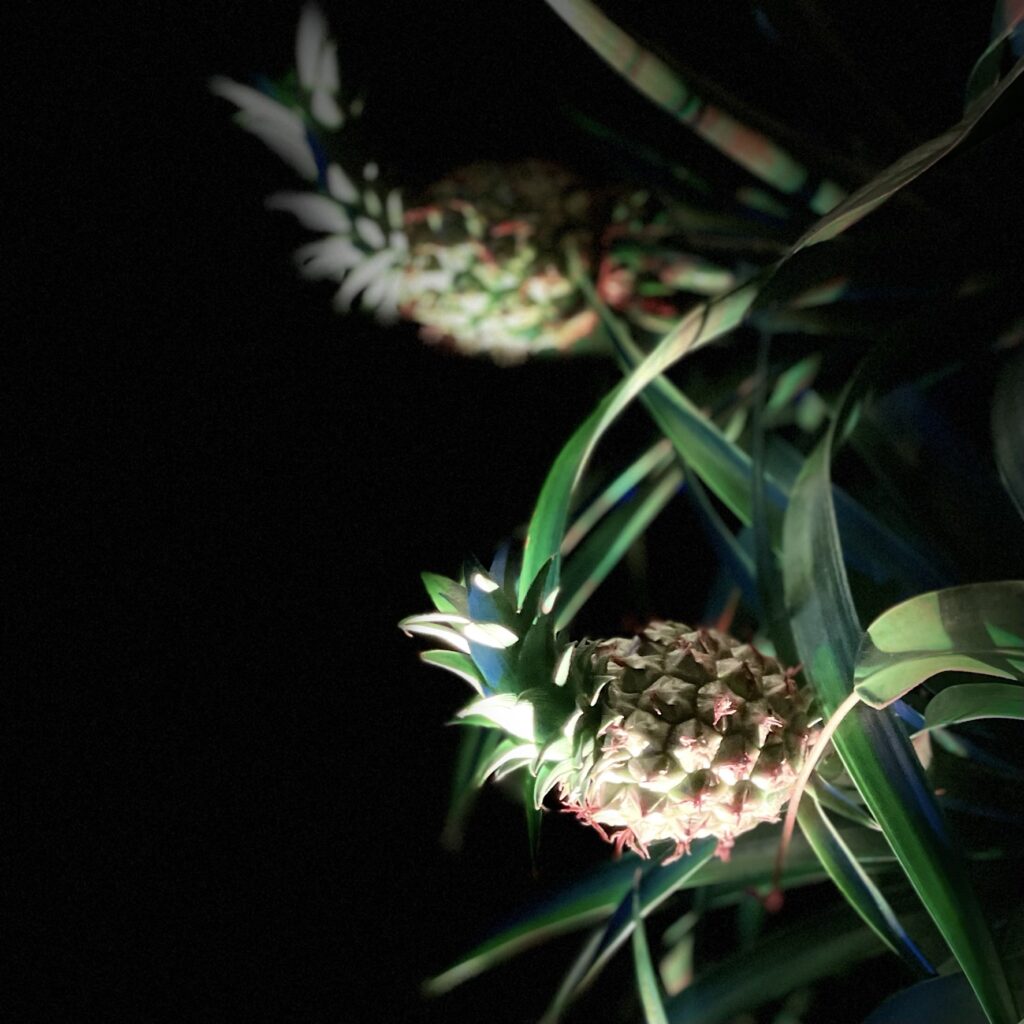

These rare flowering plants are so old that the memory of the dinosaurs flows in their veins. Orchids shared the planet with bipedal reptiles for a few dozen million years and successfully survived catastrophes and mass extinctions. Even the recent (for their species) emergence of humans, which was and is disastrous for many plants and animals, may be beneficial for orchids. Long before humans, orchids were already the most diverse family of flowering plants comprising ten percent of the total number of plant species. However, thirty-five thousand different wild orchids appeared to be not enough: they needed slightly more than only one hundred years to fascinate humans and make them create over one hundred thousand hybrids and cultivars, which colonize their indoor habitats today. Cultivable orchids are now trivial in hotel foyers, airport terminals, and homes. We can buy them in every supermarket all over the world, and robust cultivars will grow in dry environments of heated rooms and blossom there for years. They are so popular that almost all flower shops offer fertilizers and sprays for orchids, and botanical gardens celebrate their beauty by building orchid sculptures. Perfumers copy orchid fragrances for cosmetics or laundry powder aromas. Vanillin – the must-have taste for ice creams, chocolate, or other sweets, is the natural component of vanilla orchid beans. People consume vanillin in such a colossal amount that no orchids can supply enough of it. Therefore, ninety percent of this compound is now chemically synthesized from petroleum, and the vanillin market is worth at least half a billion dollars. There is no surprise that Chinese pharmacopeia lists many treatments based on orchids, and British scientists can not exclude the therapeutic role of some. For example, one can use orchids if your yin (coldness, moistness) needs to be replenished.

In the tropics, where most orchid species live in the canopy, they do not need soil. Instead, they make gorgeous gardens on the tree branches and their green roots freely hanging down. However, they are not only tropical and epiphytic. In a temperate climate, they grow in soil and can be found virtually everywhere, only maybe apart from glaciers.

Orchids’ flowers are indeed bizarre but also smart in the fashion meaning of this word. Some of them can even trick their pollinators. Flowers of some species resemble the smell and shape of female bees from a particular species. They do it so closely that males will try mating with them. I am sure that the bees do not find it disappointing and try it again and again and thus transfer pollen from one orchid to another, sometimes cheating on natural female bees. However, the orchids are not greedy and generously reward their bee friends with nectar making the bees reluctant to visit other flowers. The friendship between orchids and their pollinators is so fascinating that it was first studied not less than by Charles Darwin and became a canonical example of coevolution.

However, the most exceptional feature of orchids is that their babies parasitize on fungi. Orchids’ seeds are as tiny as spores or pollen grains. Therefore, they contain no nutrients to support their germination. Instead, they exploit (again!) mushrooms, which provide the first nutrients to orchid germlings, and are not even rewarded for it. In biology, this type of nutrition is called mycoheterotrophy, with orchids being mycorrhizal cheaters.

So, these ancient and variable plants do not need soil, can trick bees and fungi, and use humans to multiply their diversity and distribution. Isn’t this smart?

To me, orchids are no less mind-blowing than platypi, and I am very happy that many botanists are studying them. I hope their delicate beauty, gentle smell, and exceptional biological history will add to the plethora of reasons convincing people to protect not only orchids but our forests and meadows where they can grow. Let us repay our debts to these plants and allow orchids to continue their spectacular journey on planet Earth.

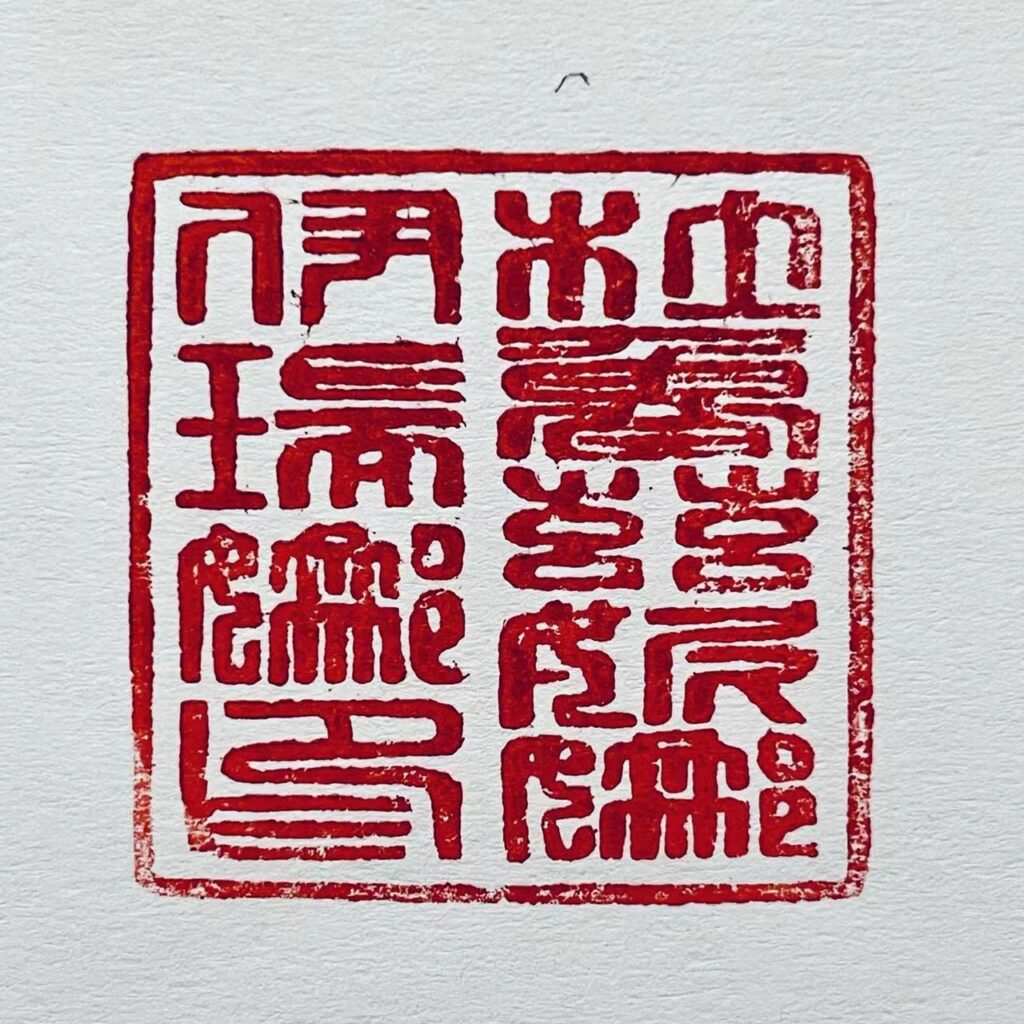

PS: Recently, I came across an unexpected “role” of orchids. An orchid in Chinese is 兰花 [lánhuā]. The last character simply means a flower, but the first one [lán] is an orchid, and it is phonetically close to [land] without the [d]. Therefore, 兰 is the right character for making polite and poetic names of, for example, foreign countries. My favorite is 爱尔兰, which literally means [love my orchid], but phonetically sounds as [ài-ěr-lán], i.e., Ireland. I wonder which orchids grow in Ireland, but I am sure they are loved there.

One can see the character 兰 [lán] in names of Finland – 芬兰 [fēnlán], Poland – 波兰 [bōlán], the Netherlands – 荷兰 [hélán], and even Ukraine – 乌克兰 [wūkèlán], but I still need to understand the last construct. Cai Feng, can you explain?